It should be noted that the below articles appeared in two local new papers, with assistance and consent of the Rigsby family. Likewise I was given permission and authority to post this information from the Rigsby family.

Wrongful-death suit arises from overdose

The woman's death was ruled a suicide, but her parents are suing the husband and his mother.

By CARY DAVIS

© St. Petersburg Times, published October 6, 2001

The woman's death was ruled a suicide, but her parents are suing the husband and his mother.

NEW PORT RICHEY -- The estate of a Hudson nurse who died of a drug overdose two years ago has filed a wrongful-death suit against the woman's husband and his mother, alleging that they caused the nurse's death.

The lawsuit, filed this week in Pasco Circuit Court, says John P. StelzI Jr. and his mother, Bette Hayes, "unlawfully and intentionally killed, or participated in procuring the death" of 26-year-old Catherine SteIzl.

Catherine Stelzl, a nurse at Regional Medical Center Bayonet Point, died in her Hudson home on Aug. 20, 1999, from an overdose of GHB, a trendy drug that acts as a depressant. Hours earlier, she visited an attorney to discuss plans to leave her husband.

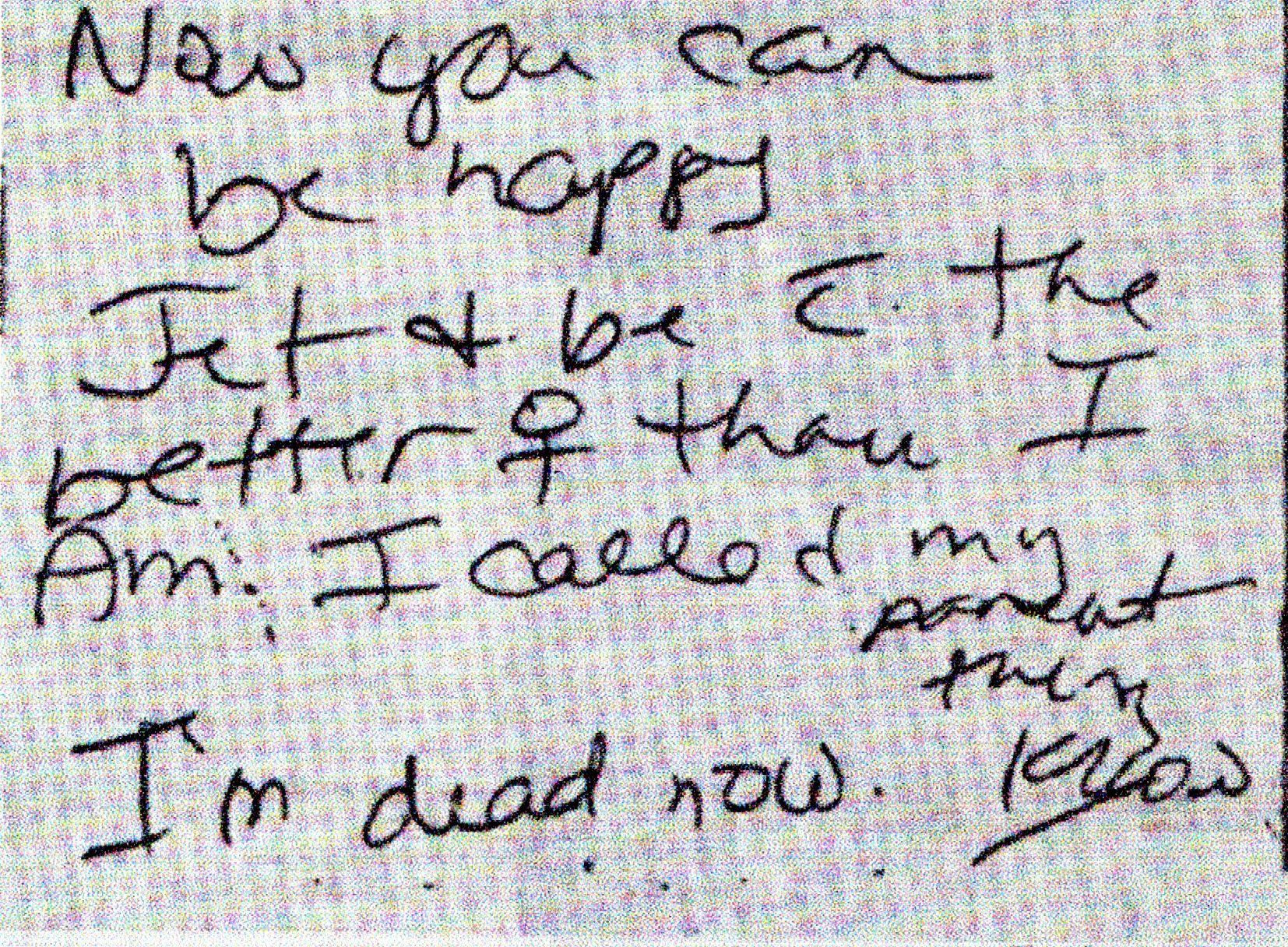

The Pasco County Sheriff's Office investigated the death and ruled it a suicide. Among the evidence the Sheriff's Office cited in reaching that conclusion was a suicide note written by Catherine Stelzl to her husband, in which she said, "Now you can be happy."

The Pasco-Pinellas State Attorney's Office also investigated the case and reached the same conclusion.

Catherine Stelzl's parents, David and Margery Rigsby, refused to accept the findings, and hired a private investigator to examine the case. The investigator, Claude Lavaron, compiled a lengthy report, which he sent to the St. Petersburg Times, that lays out a circumstantial case against John Stelzl and suggests that he received help from his mother, Bette Hayes.

Prosecutors and the Sheriffs Office reviewed Lavaron's findings and determined there was no evidence of a crime.

The parents cited Lavaron's findings in asking Circuit Judge Lowell Bray to disqualify John Stelzl as an heir of his wife's estate. John Stelzl did not respond to the allegations in the probate case. As a result, Bray in June made the finding that StelzI intentionally caused his wife's death. The judge's ruling disqualified John Stelzl as a beneficiary of his wife's estate, which included a $100,000 life insurance policy.

Neither John StelzI nor Hayes could be reached for comment Friday.

The lawsuit seeks damages in excess of $15,000.

_______________

Tampa Tribune

Sunday September 15, 2002

Who killed Catherine?

By CANDACE J. SAMOLINSKI

By CANDACE J. SAMOLINSKI

csamolinski@tampatrib.com

Photo by: CHRISTINE DeLESSIO

David Rigsby of Kentucky has made dozens of trips to Florida in a quest to find out how his only daughter, Catherine, 26, died Aug. 20, 1999. The Pasco County Sheriffs Office has ruled Catherine's death a suicide.

HUDSON, Florida- “Daddy, I'm in love."

David Rigsby of Kentucky remembers hearing those bittersweet words when he stood on a Pasco County beach Oct. 23, 1998, and gave away his only daughter, Catherine, to her groom, Johnny Stelzl.

Their 10-month fairy tale courtship left Catherine, who had always been self-conscious about her weight, feeling lucky to have been chosen by the muscled, blond Stelzl.

Rigsby pooled his savings to pay for their reception and a Hawaiian honeymoon cottage, but he worried his little girl had fallen into the hands of a master manipulator.

Nine months into the Stelzls' marriage, Rigsby hired a private investigator. What Rigsby and his wife, Margery, learned about their son-in-law kept them awake at night, and a month later, Catherine gathered the courage to seek a divorce.

The decision came too late.

On Aug. 20, 1999, Stelzl called Rigsby to tell him Catherine was dead at 26. 'Check your answering machine" was the cryptic way he opened the conversation.

Three years and $150,000 later, this working-class father has devoted himself to keeping a promise to Catherine's memory to find out what happened.

Rigsby has made dozens of trips to Florida, financing the investigation with his job as an internal policy analyst.

He's taken on the Pasco County Sheriffs Office, which ruled Catherine's death a suicide. In January 2001, Rigsby's attorneys persuaded Circuit Judge M. Lowell Bray Jr. to declare Stelzl responsible for Catherine's death in a civil probate lawsuit.

Stelzl, who stood to inherit Catherine's $100,000 life insurance policy until Bray awarded the money to Rigsby, was never criminally charged.

Now, Rigsby finds himself chasing a ghost.

Stelzl, 33, died Oct. 24, 2001, in Pinellas County in what was ruled an accidental drug overdose.

Rigsby was so certain Stelzl would do anything to get away with murder that he sent a private investigator to Stelzl's funeral to make sure it was him in the casket.

Assembling A Puzzle.

Catherine died of a GHB overdose at the couple's home on Partridge Hill Row in Hudson. Her mother-in-law, Bette Hayes, called 911 after finding Catherine naked in a bathtub filled with water.

Stelzl never came to the home after being notified. He didn't show up at the hospital as paramedics were trying to save Catherine.

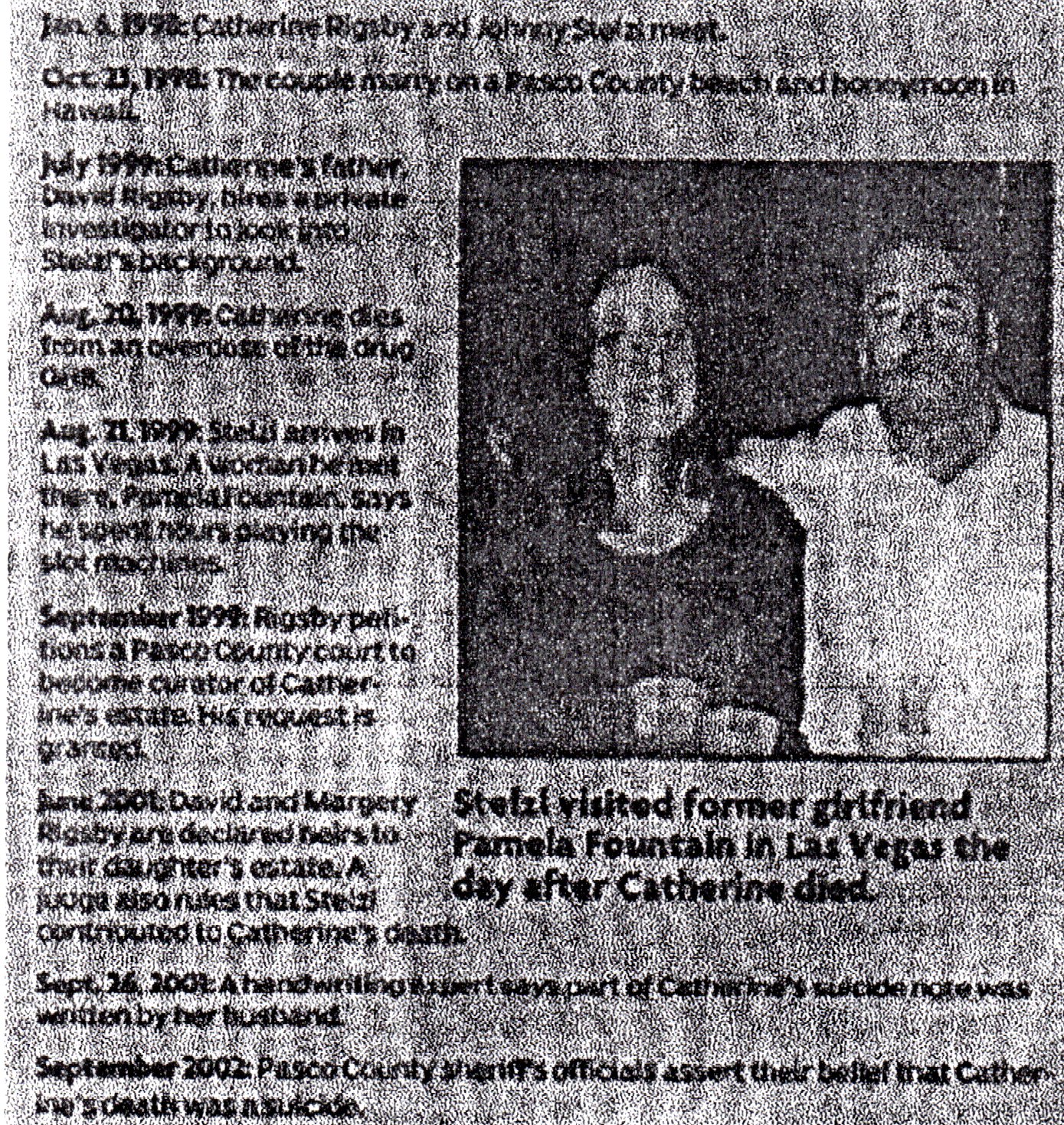

The next day, Stelzl flew to Las Vegas to visit a former girlfriend, Pamela Fountain.

Since Catherine's death, Rigsby and investigator Claude E. Lavaron of St. Petersburg have amassed a mountain of circumstantial evidence they say points to SteIzl as her killer.

However, a sheriffs detective and his supervisor have dismissed the findings after twice conducting investigations. Prosecutors support the sheriffs decision.

Rigsby's quest for answers ignited after he followed Stelzl's advice and listened to his answering machine, which contained three messages from Catherine. The messages left during a 20-minute period reveal a gamut of emotions, beginning with Catherine's optimism about her decision to divorce Stelzl and ending in resolute sadness about her inevitable death.

"He told me she left these messages before she died. There is no way he could have known about those messages unless he was in the house when she left them," Rigsby says. When he called again, he said, Like she said, she's in a better place.' How could he have known she used those exact words?"

Stelzl, who was arrested in the months after Catherine's death on an unrelated warrant, told Pasco Detective I.R. Law that he used a code he found in his wife's bank book to retrieve messages from Rigsby's answering machine. However, when questioned, Stelzl was unable to recall the code or how many numbers it might have contained.

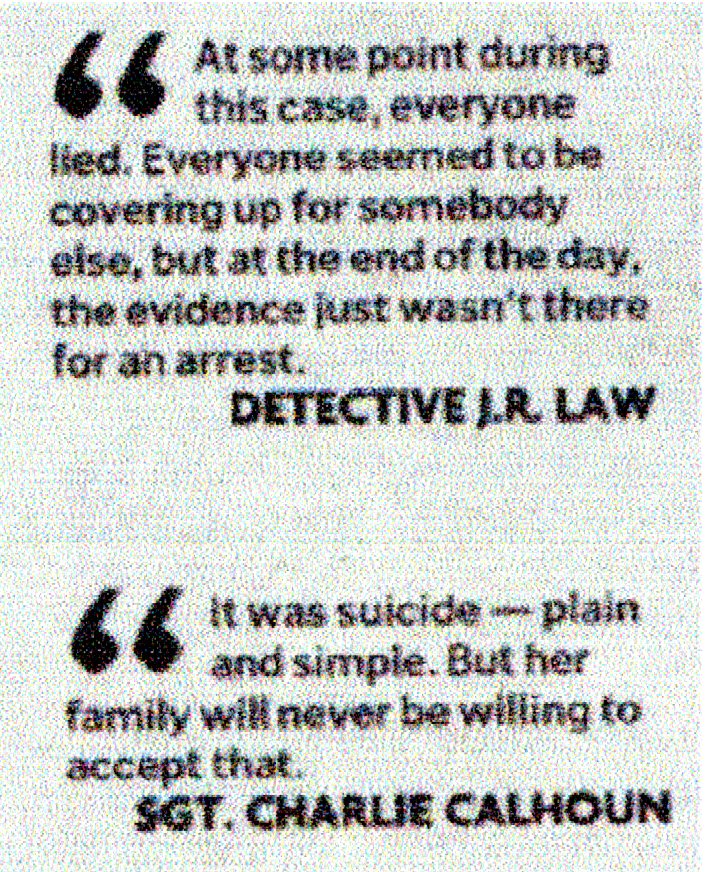

"At some point during this case, everyone lied," Law says. Everyone seemed to be covering up for somebody else, but at the end of the day, the evidence just wasn't there for an arrest."

Rigsby questioned the authenticity of a suicide note attributed to Catherine, and he began to believe Stelzl had forced her to take GHB.

This wasn't Catherine's first encounter with gamma hydroxybutyric acid, her father says. Rigsby recalls Catherine said Stelzl asked her to try it to improve their sex life. She also said the drug left her unconscious.

GHB is an illegal clear liquid commonly used as a weapon of sexual assault. It causes intoxication, suppressed respiration, vomiting, uninhibited behavior, coma and death.

Investigators doubt Catherine was forcibly drugged because there were no signs of a struggle, Law says. However, Rigsby says he believes deputies missed a key piece of evidence. They failed to take into evidence a glass that had been sitting near the bathtub when paramedics arrived. It was broken during rescue attempts.

Rigsby says the glass could have shown Stelzl's fingerprints and GHB remnants, although Law says that wouldn't be conclusive evidence that Ste1z1 drugged Catherine.

Speculation about Stelzl's involvement also was fueled by the results of a handwriting analysis Rigsby requested on the suicide note.

Richard Orsini of Jacksonville, a court-qualified document examiner, compared the note to samples of Catherine's and Stelzl's handwriting. He concluded at least part of the note was written by Stelzl.

Law and Sgt. Charlie Calhoun say such information may have held up in civil court, but wouldn't have resulted in a criminal conviction.

A Tainted Past

When Rigsby started his investigation, he didn't expect to find a web of deceit that began before the couple's marriage.

Rigsby knew Stelzl had been married before, although Stelzl indicated he hadn't on the license application to marry Catherine.

Stelzl had married Michelle Douglas in 1986 and is listed as the father on the birth certificates of her three children. He later gave up his parental rights, records show. Douglas, formerly of Brandon, says in divorce documents that she endured emotional, physical and sexual abuse by SteIzi and saw him use illegal drugs.

Rigsby also uncovered Stelzl's extensive criminal history.

Between 1986 and 2001, he spent time in county jails and state prison for larceny, robbery, grand theft, cocaine possession and aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.

Detectives say letters exchanged between Catherine and her husband show she knew about his past. However, the sheriffs office was unable to produce those letters.

Rigsby learned even more from the woman who welcomed Stelzl to Las Vegas less than 24 hours after Catherine's death. Las Vegas homicide detectives questioned Fountain at Law's request.

Fountain, 39, says StelzI swept her off her feet and proposed on New Year's Eve 1997, a few months after they met in Las Vegas while Stelzl was helping a friend move.

But in January 1998, Stelzl met Catherine.

"When I first met the guy, I thought he was like way out of my league," Fountain told Las Vegas detectives.

"Cause he was like this bodybuilder, and you know, he's pretty attractive and stuff. And I'm kinda heavy, and I thought, you know.... But when he started like calling me a lot, and sending me these presents, and bought me a ring and stuff, I was like, oh my God ... he was just in love with me."

SteIzl returned to Florida, and their relationship continued until Fountain found out about Catherine.

"A few days before he married Cathy, he called me and was like, miss you. I love you so much,' " Fountain recalls.

A week after the wedding, Fountain received another telephone call. This one was from Stelzl's mother, Hayes, of Spring Hill.

"Bette said, 'If I paid for Johnny's marriage to be annulled, would you take him back? " Fountain says. said "that I couldn't trust him."

During the next few months, Fountain says, StelzI told her about buying expensive cars, a personal watercraft, a boat and a house. His mother complained to Fountain that Catherine 'was only out for his money."

Financial records show the items were purchased on Catherine's credit.

Hayes declined to comment for this story.

During Stelzl's last trip to Las Vegas, after his wife died, Fountain says they went to a casino where he withdrew $300 from an ATM and later charged a dinner at Red Lobster. This money came from one of Catherine's credit cards, financial statements show. Fountain said StelzI spent hours playing $1 slot machines and had money to burn.

Catherine's Official Image

In July and August 1999, deputies twice were called to Catherine's aid, and each time Hayes and Stelzl were waiting to offer information, sheriff's reports state.

They portrayed Catherine as an unstable young nurse who stole drugs intended for her patients, abused prescription drugs at home and who had been hospitalized twice because of drug overdoses.

Law and Calhoun say this was an accurate picture, and point to statements from a co- worker who also said Catherine stole drugs. That nurse later was arrested and convicted of stealing Vicodin, a painkiller, from the hospital.

On the day of Catherine's death, Hayes told deputies this was Catherine's third suicide attempt. She recounted a horrifying scene" in April 1999 when her son found Catherine lying in feces and vomit after ingesting GHB, and rushed her to Regional Medical Center Bayonet Point in Hudson. She said her daughter-in-law demanded to leave the hospital in fear her career as a registered nurse there would be in jeopardy.

The hospital has no record of the visit.

Law and his supervisor say doctors were "covering for one of their own." Hospital administrators deny a coverup.

Hayes also told deputies of a second suicide attempt in July 1999. This time, she said, StelzI took his wife to North Bay Hospital in New Port Richey.

A sheriffs report confirms that visit and gives the following account.

StelzI identified himself to doctors as John Rigsby. A nurse called the sheriffs office to report the overdose. A deputy arrived, spoke to Hayes and was told Catherine was a prescription-drug abuser. The deputy ran a computer check on John Rigsby, Catherine and Hayes.

If the deputy had known Stelzl's true identity, he would have learned StelzI had a warrant on a violation of probation charge from Citrus County.

StelzI told the deputy his wife recently had visited Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, and bought the drug Temgesic - a painkiller that requires a prescription in the United States. The deputy asked to search their home in order to show no signs of foul play" and questioned whether these drugs were illegal, sheriff's reports state. StelzI demanded an attorney. The deputy called a prosecutor, who refused to request a search warrant. The matter was dropped.

After Catherine revived, she told a doctor, 'I really do not want to kill myself."

The doctor wrote in notes: "Mood appeared to be in a lot of stress, depressed mild, but denies any suicidal or homicidal ideation. She has good insight and good judgment."

An Untimely End

The day she died, Catherine took great pains to conceal her meeting with divorce attorney Charlene Murphy. She showed up early for work, and midmorning she borrowed a car from a co-worker, Mena Dente, and drove to Murphy's office.

A few days before, Catherine had written in a journal a detailed description of her life with StelzI. She gave Murphy a copy and a second copy was later discovered by Law in her hospital locker.

The journal details a marriage in decline. Catherine's life spiraled into a pool of emotional and physical abuse and financial ruin. The writing contains much of the information she previously had confided to Dente and to Loretta Mercer, a clinical social worker with whom Catherine had two appointments.

Dente, Murphy and Mercer say their statements were incorrectly recorded by Law and skewed to make it appear they believed Catherine committed suicide.

In Murphy's case, the detective's report indicates Catherine told her she was injecting herself with drugs. Murphy has denied making that statement.

Law stands by his report.

I have had an opportunity to work with a number of abused women," says Murphy, who practices law in Tampa. "Cathy's factual case that she laid out for me was probably the most horrific I had ever heard."

Catherine recounted being forced to have anal sex with Stelzl, drink his urine in order for him to give her money and drink elixirs he prepared for her, her attorney said, Catherine suspected StelzI was using steroids and other drugs.

She told Murphy that Ste1z1 asked her to inject him with drugs, which would sometimes render him unconscious. Catherine said she stole a heart monitor from the hospital because she feared he would die. She recounted other times when a violent Ste1z1 would put her in a headlock until she nearly fainted.

Law says it is common for women planning a divorce to exaggerate abuse if they feel they will benefit financially. There are no police records indicating Catherine reported abuse.

After leaving Murphy's office, Catherine drove back to the hospital and thanked Dente for lending her the car. She said she was going home to pack some things, then would go to the courthouse to follow Murphy's advice to get a domestic-violence injunction.

Her spirits seemed high when she left at 12:45 p.m., Dente said.

By 5:45 p.m., Catherine was dead. She never made it to the courthouse.

“It's not a question of whether Cathy committed suicide; she didn't," says Mercer, her therapist.

Lingering Questions

Records show Hayes called 911 at 4:43 p.m. to report her daughter-in-law's overdose. When deputies arrived, Hayes said she was unable to reach her son.

A court deposition shows Hayes gave the following account:

Between 12:30 and 2 p.m., Hayes got a call from Catherine, who said ' ' she didn't want to live anymore." However, Hayes told detectives that call came between 2:30 p.m. and 3:40 p.m.

Hayes said it took her one to two hours to drive the 16 to 20 miles from Spring Hill, where she worked as a home health care nurse, to her son's home.

Hayes went inside and called for Catherine. She found her unconscious and naked in a bathtub filled with water. She said she let out the water and attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation. She said she found a knife in the tub. Her description of the knife varied in sheriffs reports and court records. Hayes said she moved the knife, but couldn't remember where she put it.

The knife was later taken into evidence, and it isn't clear in records where a deputy found it.

Hayes followed as paramedics took Catherine to Regional Medical Center Bayonet Point. Deputies returned to the house with Hayes after Catherine was pronounced dead.

Hayes told deputies she didn't have a key, so they couldn't go back inside. Deputies left the house.

At 3:30 a.m., neighbors of the Steizls reported seeing Hayes loading bulging garbage bags into her car. Hayes said she did this at her son's request.

In the weeks following, Hayes rented a U-Haul and cleaned out the home. Then she held a yard sale at her Spring Hill home.

Rigsby and Lavaron, the private investigator, questioned Hayes' timeline of events and her inability to reach StelzI. They requested the call histories for Aug. 20, 1999, from cellular phones and home telephones belonging to Hayes, StelzI and Catherine. They found no call to Hayes from Catherine the day she died, but they found several calls between mother and son, and SteIzl and Fountain.

Law and Calhoun have called those records incomplete, but they never requested copies.

When Stelzl returned to Florida from Las Vegas three days after Catherine's death, he ordered her cremated. Her wedding dress and most of her ashes were returned to Rigsby in September 2000.

The majority of ashes were scattered Nov. 30, 2000, in the Memorial Garden of her church, Universalist Unitarian in Lexington, Ky., and a smaller quantity were later released on Stradbroke Island, Australia, in 2002.

Despite Rigsby's requests, Stelzl never returned most of Catherine's jewelry. Pawnshop records bearing Stelzl name, obtained by Lavaron about a year after Catherine's death, showed StelzI pawned several pieces of jewelry that matched items missing from her home after her death.

Pasco investigators say they are finished with Catherine's case and have no plans to reopen it, but Rigsby vows to keep pushing for justice.

"It was suicide - plain and simple," Calhoun says. But her family will never be willing to accept that."

Reporter Candace J. Samolinski can be reached at (813) 9.18-4213.

This story can be found it http://tampatrib.com/MGA120MF46D.html

________________

Tampa Tribune Pasco Edition Oct 7, 2002

Catherine Stelzl Deserves Justice

By CLAUDE E. LAVARON III

Tampa Tribune reporter Candace Samolinski did a good job reporting the very complicated and sensitive case of Catherine Stelz1 (` 'Who Killed Catherine?) (Sept. 15). We appreciate her efforts and commend her professionalism and objectivity.

As the investigator for the Rigsby family, I feel compelled to point out several facts that Ms. Samolinski was unable to include, despite the generous space Tribune editors allocated for this complex story.

Pasco sheriff's Det. Sgt., J.R. Law was reassigned to organize the Pasco Department of Children and Family division in Dade City about 2 weeks after Catherine's death. Despite this new assignment, he remained the homicide detective assigned to this case, which occurred some 30 miles across Pasco County.

The Pasco sheriff's office did not follow standard policy and procedure to investigate Catherine's death as a homicide until the facts and circumstances clearly established otherwise.

Pasco issued a be on the look out" alert for Johnny StelzI on Aug. 25, 1999, stating he was wanted for questioning in the death/apparent suicide of his wife, Cathy." This declaration seems to indicate the sheriff's office had decided Catherine committed suicide even before they talked with her husband, and before any reasonable effort was made to collect evidence regarding the facts and circumstances surrounding her death.

Why?

Perhaps the determination to rule her death suicide had less to do with Catherine and more to do with the sheriffs office.

The sheriff's office never declared Catherine's residence, where she was found in cardiac arrest, a crime scene. The sheriffs office never called a forensic unit to collect evidence and document the crime scene. The sheriff's office never photographed or videotaped the bathroom or the residence where Catherine was found.

The sheriffs office never collected glass discovered near the bathtub where Catherine was found. A sheriffs deputy later advised the medical examiner that no glasses of liquid or alcohol were found at the scene." He did not advise that a glass had been found near Catherine, broken at the scene, and left behind.

Within one hour of arriving at Catherine's residence, deputies relinquished control of the scene. They were later denied re-entry by Johnny Stelzl's mother, Bette Hayes, who claimed she did not have a house key and that a key was not on Catherine's key ring.

The sheriffs office never processed fingerprints on a large serrated knife found in the bathroom, despite requests from the family and my office. The sheriff's office never processed the alleged suicide note for fingerprints or had it analyzed by a handwriting expert, despite requests from the family and my office. They also did not reveal or document that the note was folded, and had been for some time, to the size of a man's wallet. They also did not document that the initials 'JS" appear twice on the back.

The sheriffs office never requested the Pinellas-Pasco Medical Examiner's Office test Catherine's body for GHB, or gamma hydroxybutyric acid, despite requests from Catherine's family and knowledge that Johnny StelzI was an admitted GHB user.

For eight months, the sheriffs office assured the Rigsby family that GHB testing was included in the regular toxicology, while it erroneously advised the medical examiner that Catherine previously overdosed on diet medication. She had never overdosed on diet medications.

My firm, EX-CEL Investigations, interceded with the medical examiner and requested the GHB test. A massive amount of GHB ... had killed Catherine.

The sheriffs office never interviewed Catherine's supervisors or immediate co-workers at Bayonet Point Regional Medical Center. Only those who contacted the sheriff's office received an audience. Of those, three have signed statements that they were misquoted; that their descriptions of John Stelzl's behavior was attributed to Catherine; or that pertinent information supporting Catherine's mental stability and lack of suicidal ideation was omitted from the reports.

These are in addition to misquoting Catherine's attorney on a statement reflected accurately in Catherine's journal describing Stelzl's abuse and drug use - a journal the sheriff's office had already taken into evidence.

The sheriffs office never interviewed hospital administrators to confirm that Catherine was not stealing drugs. It also has insisted that one of Catherine's co-workers claimed she was stealing drugs, when in reality they allegedly received this information from an emergency room nurse who neither knew nor worked with Catherine.

The sheriff's office never interviewed a Bayonet Point Regional Medical Center nurse who claimed to have called Johnny Ste1z1 on his cellular phone the day of Catherine's death and alleged that he told her 'Cathy is gone," some five hours before she died.

The sheriff's office never interviewed Johnny Stelzl's former wife or another girlfriend, instead claiming that they could not provide any useful information. When a Bayonet Point Regional Medical Center security guard contacted the sheriff's office, advising Johnny SteIzi might be in hiding with the other girlfriend or her relative, no follow-up was made or documented regarding apprehension attempts.

The sheriff's office never grasped the significance of Johnny Stelzl's conflicting claims (given in a jailhouse interview and later in deposition) as they related to his purported access to the Rigsby's answering machine. Neither SteizI nor Hayes had the access code; nor did either provide the accurate code. The code was never provided to Catherine, who SteizI alleged was his information source.

The sheriffs office reports claim that a $101,000 insurance benefit would not be paid on Catherine's death. It had been paid 11 months earlier and was secured in Catherine's estate under control of a neutral, court-appointed attorney serving as personal representative.

In addition, the reports omit that Johnny discussed insurance proceeds in Las Vegas, where he [went] 3 days after Catherine's death.

The sheriff's office never interviewed the probation officer supervising Johnny StelzI after Catherine's death. The officer stated Johnny SteizI bragged to him and others about his plans for the money he would receive from Catherine's estate. The sheriff's office was aware of the pending civil suit to determine Catherine's heirs but never reviewed the court files.

Rather than believe Catherine's family, friends, professional colleagues and documented evidence, the Pasco sheriffs office chose to accept proven fabrications.

The Pinellas-Pasco Medical Examiner's final report lists the manner of death as undetermined." How can the Pasco County Sheriffs Office disregard the medical examiner's report and call Catherine's death a suicide when they have no facts to substantiate that determination?

As a former Florida law enforcement officer and a Certified Legal Investigator with more than 30 years' investigative experience, I view the issues and inconsistencies in this case as unacceptable. Unofficial reviews by numerous professionals in the legal and law enforcement community, both in Florida and beyond, have been similarly critical.

The Florida Attorney General should require that an independent agency look into this matter and let justice be served. For without the facts, there can be no justice.

The writer is a private investigator whose firm is based in St. Petersburg.

This story can be found at:

http://tampatrib.com/pasconews/MGALOZJRZ6D.html

I am please to say as of 2011, Pasco County now has a great new Sheriff, Chris Nocco who was appointed by then Florida Governor Rick Scott. Sheriff Nocco was then elected to that position in 2013 and again in 2017. Pasco is fortunate to have him, as he is dedicated to all of the people in Pasco County.

The Law firm of Deane & Hinton was the attorney or record in this case and represented the Rigsby's in the legal matter. They did a great job in presenting the evidence to the court and was successful in have the court award the Rigsby's the $ 101,000.00 in insurance proceeds.

Deane & Hinton

1597 62nd Avenue North

St. Petersburg, Florida 33720

727-576-8811